Part

01

of one

Part

01

Healthy Food Movement

Food Banks & Pantries in the United States and Wisconsin are overwhelmed. They were never designed to be a daily source of food security for millions of Americans. These organizations are responding to the crisis by partnering with multiple stakeholders, including other food banks and pantries outside of their original network. Most social service organizations dealing with food and nutrition issues do not disclose many details surrounding their structure, internal and concerning other institutions. However, they usually maintain the same basic structure (governance, administration, and programs). Memberships and coalitions are essential, especially now. Federal and state grants typically account for the bulk of funding, except for Northwest Harvest, which actively seeks to remain independent.

United States

- Food banks and pantries are facing unprecedented challenges that go beyond their original purpose. To understand how they are evolving, it is worth looking into the current situation.

Food Insecurity in the United States

- Prior to the pandemic, 10.5% of all American households experienced food insecurity at some point of the year, accounting for over 35 million people. COVID-19 severely worsened the problem, with researchers from Northwestern estimating that 23% of households in the United States were affected by food insecurity in 2020.

- The situation is worse for households with children. An analysis by the Brookings Institution “conducted earlier this summer found that in late June, 27.5% of households with children were food insecure — meaning some 13.9 million children lived in a household characterized by child food insecurity. A separate analysis by researchers at Northwestern found insecurity has more than tripled among households with children to 29.5%.”

- The government assistance and extended SNAP program failed to meet the United State’s food security needs. As a result, Americans turned to food banks at a rate greater than the 2008 recession. The number of "people in the U.S. enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in 2020 spiked to nearly 44 million from 35.7 million a year earlier amid a reeling economy." However, the program is entirely not covering their needs. Nearly 40% of food bank clients are enrolled in SNAP.

- "Shortfalls in these programs put extra pressure on food banks during the pandemic. And the effects of these deficits are not just short-term, says Megan Sandel, co-director of the Grow Clinic for Children at Boston Medical Center. She says she has seen a 40 percent increase in her caseload, with over two-thirds reporting food insecurity."

The Impact on Food Relief Organizations & Communities

- According to Brian Ronholm, Consumer Reports’ director of food policy, the situation is much worse than the 2008 crisis. He adds, “When you factor in the economic crisis caused by the pandemic and combine it with the food-supply disruptions that have occurred, it’s created almost a perfect storm for food insecurity.” Even with Biden’s plans to expand federal assistance, analysts believe the United States will struggle with food insecurity, and the burden is expected to fall on food banks.

- As the pandemic progressed, food banks became "more visible than ever before." Between March and November 2020, they provided the equivalent of 4.2 billion meals, with over 80% reporting that they are now supporting more people than before. Feeding America, the largest food bank network in the country, saw “an increase of 64 percent from a typical pre-pandemic month” in August. For many Americans, food banks became a lifeline.

- At the same time, food costs increased and “reclamation products” diminished drastically. "Food banks and pantries don’t get all their food from donations. When they have to buy it, they can get better prices than consumers because they buy in bulk and don’t pay sales tax. But food prices have gone up for nonprofits, just as they have for regular folks."

- There are also added costs, such as electricity, boxes, forklifts, among others. Food banks also had to deal with shortfalls in funding. Rossman of Neighborhood House explains, "Our normal donor base has given to its capacity. Some of my board members have been furloughed. These are professionals in the community above middle class, and they are getting crunched, too."

- Additionally, the pandemic changed the way food banks operate due to safety concerns. "Requirements for social distancing and contactless handoffs require volunteers to fill prefabricated boxes, a more laborious process." However, the number of volunteers also dropped significantly. Food banks in multiple states report a severe drop in the number of volunteers, sometimes up to an 80% decrease. Furthermore, when volunteers are available, they have to be limited to address social distancing concerns.

- There are also issues with the disparity between regions. Feeding America reported that food banks in metropolitan areas received more private donations, while smaller ones struggled to gather resources. "The larger food banks, like Boston and Houston, are experiencing greater philanthropy, but smaller ones haven't had as much success," she says.

- Food banks & pantries were not equipped to handle the current situation; they were never supposed to be the primary food security source in their regions. Nonetheless, they ended up "shouldering a two-fold burden since the pandemic began: supporting the millions of Americans newly facing food insecurity, who don't participate in or don't qualify for SNAP, while also serving those already receiving assistance that doesn't get them through the month."

- Stacy Dean, the new deputy undersecretary for food, nutrition, and consumer services at the Agriculture Department, recognizes that food banks have stepped up to meet Americans' needs. She also notes that they can in fact address emergencies rapidly, but "in this environment, they have been asked to do so much more, which is to provide food for longer periods of time and to supplement the federal food programs." That goes beyond the capabilities of these organizations.

- Brian Barks, president and CEO of Food Bank for the Heartland, illustrate a situation shared by other banks as well, saying "It is taking every ounce of energy that we have in order to try to help those people who have been added to the rolls of those who are now food insecure," he stated, "Anything, anything that can be done to alleviate the pressure that food banks are facing, to purchase and distribute food will benefit the hunger relief organizations in a positive way."

How Food Relief Organizations are Addressing the New Challenges

- To address this situation, a growing number of food banks are partnering with "social service and health care providers, insurance companies, universities and businesses to provide an array of support for people who are experiencing food insecurity. This includes transporting people to food pantries and helping them enroll in federal and state food assistance programs as well as food prescription programs, health promotion and disease prevention programs, and job training. Some examples of new partnerships:

- Facing disruptions caused by the pandemic, many banks noticed that historical data would not efficiently calculate future needs. Some, like the Second Harvest Heartland, turned to data to re-route its operations. “Second Harvest Heartland partnered with McKinsey to develop a demand model to forecast the supply that it would need, based on various scenarios of future demand.”

- Another organization that worked with McKinsey to optimize its warehousing operations was Feeding America, the country's largest food bank network.

- Loaves and Fished partnered with Lyft to create a transportation program for food-insecure households. United Way partnered with DoorDash to create the Ride United Last-Mile Delivery Initiative, providing "delivery services from local food banks, food pantries, and other distribution points to older adults, low-income families, and those who can't leave home, providing meals to those in need." The program, funded by The Rockefeller Center and Safeway Stores, servers more than 175 communities.

- Several food banks and food security organizations are partnering with healthcare providers in referrals and food prescriptions programs. For example, when someone is screened by a Food for Change’s healthcare partners, they get a food prescription named Food Rx, which can be redeemed for fruit and vegetables, and other healthy items.

- Additionally, networks, associations and coalitions that provide communication and partnerships between the banks & pantries are proving their value. Several regions, such as Washington, launched coordinated efforts to ensure all vulnerable households are efficiently covered. For example, Capital Area Food Bank works with 450 direct distribution and nonprofit partners.

Projections

- Charities are noting that they "continue to see generosity in the form of volunteer work, food, and money, which they hope will last beyond the traditional holiday season. But solving food insecurity is a problem of a much bigger scale than what they can handle"

- The outlook for food banks and pantries in the United States is not great. Feeding America projects a "6 billion to 8 billion meal shortfall in the next 12 months," which will leave many Americans food-insecure."

- Nonetheless, Columbia University researchers "estimate that a combination of Biden’s proposals could reduce poverty in 2021 by almost 30% and halve the number of U.S. children living in poverty. If successful, this could launch a longer-term transformation in anti-poverty policies."

Wisconsin

- Wisconsin is following similar patterns as the rest of the country. The increased demand is burdening food relief organizations. Volunteer numbers have not gone back to pre-pandemic levels yet, but leaders expect the extended federal government support to provide some much-needed relief. Public-private partnerships are booming, as well as collaboration among different non-profits. Organizations are focusing on local suppliers/partners to minimize disruptions.

- The state's most notable difference was the Civic Response Team, which was excluded from the report given previously noted awareness surrounding the organization. If more information surrounding the Civic Response Team is desired, the Collective Impact Forum published a detailed case study that examines its development and actions.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Banks & Pantries Statewide

- The pandemic's first months were chaotic for food relief organizations in Wisconsin, as demand spiked while volunteer numbers dropped and supply chain disruptions limited access to resources. By June, USDA supplies started to come in, and the situation stabilized as relief checks also helped the population. Still, sources were limited, and excess food from farmers' markets and restaurants, which are usually essential sources for these organizations, were not coming in at the same rates.

- By October, demand was high once again. Sherrie Tussler, executive director of the Hunger Task Force, explains, “I have never seen any circumstances as bizarre and complicated as what we’re seeing right now.”

- By the Holidays, Food Banks in the state needed more donations since the pandemic had raised food insecurity rates by 40%. According to Second Harvest, "the number of food insecure people in Wisconsin has risen 207,570 since the pandemic began — making the total now 723,500. The jump is particularly pronounced in children, now one in five kids in Wisconsin are facing hunger."

- In December, food relief organization were greatly concerned about the expiration of federal aid. The Biden's administration extension of the federal aid in 2021 was celebrated by food banks & pantries.

- The Governor estimates that the pandemic resulted in an additional 140,000 people in Wisconsin enrolling in the FoodShare program in 2020 (SNAP program-equivalent).

- The Hunger Task Network reported distributing 30% more food in 2020 than in 2019. Meanwhile, Patti Habeck, CEO of Feeding America Eastern Wisconsin, stated that her organization saw a 40% increase in the number of people it serves.

- Shelly Fortner, executive director of the Hunger Task Force of La Crosse, "said her organization also faced added costs when distributing 20,000 of the food boxes last year in La Crosse, Monroe and Vernon counties. She said they also saw quality problems at times, like the cardboard boxes not being strong enough for the amount of food in each package."

- In January 2021, the Office of the Governor declared a State of Emergency and Public Health Emergency due to new strings, and to ensure the population would have access to FoodShare.

- Second Harvest Impact Report provides a glimpse into the work of food banks and pantries in Wisconsin:

How Food Banks are Changing to Address the New Challenges

- Following a national trend, food banks and pantries in Wisconsin are developing outreach and advocacy programs.

- Second Harvest upped its "mobile food pantry routes, which bring food to people who can’t make it to their permanent locations. Tazelaar estimates they’ve added about 17 new 'pop up' routes to their typical 28 or so a month, which have either been additional appearances in the same location or the addition of new locations."

- The Farmers to Families food boxes have been a great resource for Wisconsin's food relief organizations.

- Partnerships between different banks and other institutions are also becoming the norm.

Projections for the Future

- In Wisconsin alone, it is estimated that over "800,000 people may face hunger this year, many for the first time—an increase of around 300,000 people due to the pandemic. This would increase the rate of food insecurity in Wisconsin from 8.9 percent of the population to 13.9 percent of the population and would mean that about 1 in 4 Wisconsin children are experiencing food insecurity."

- Habeck and Fortner both noted that one of the biggest challenges their organizations have been facing is the lack of volunteers. "We have seen a decrease in volunteers for almost a year, and that really hurts nonprofits like us because we rely heavily on volunteers to help distribute food and pick up food and generally operate," Fortner said.

- According to Tussler, the pandemic complicated food distribution, and “food banks alone cannot be the answer,” she added.

Case Studies

- The information presented in the case studies varies according to the organization. There are significant differences in how much each organization divulges, apart from basic financial statements. For the “part of a continuum care program,” we presented three options, as the definition could encompass a spectrum of organizations: one Community Action organization and its CoC program in Minnesota, The Wisconsin Balance of State Continuum of Care (WIBOSCOC); one national organization that is part of multiple CoC programs; and one local organization that is part of its local United Way program.

Food Policy Organizations

Northwest Harvest

- Northwest Harvest (NWH) is the leading hunger-relief agency in Washington. It believes in equity-driven food justice. According to the organization, “advocacy is an essential ingredient for ensuring that everyone in Washington has equitable access to nutritious food. People living with hunger help us identify the policy changes they feel are most crucial to improving their access to public resources that help them meet basic nutrition, health, and housing needs.”

- NWH is an independent 501(c)(3) organization. For the fiscal year of 2019, it raised $62 million from donated food & in-kind support (68%) and cash donations & other revenue (32%). It follows the traditional non-profit structure, with a board of directors (governance), administration (leadership/executive support staff), and departments related to programs & volunteers.

- More than 70% of its funding comes from individual donors, with no individual accounting for more than 0.5% of its total annual operating budget. CEO Thomas Reynold explains that this “independence and autonomy allows us to provide food to anyone who asks.”

- Northwest Harvest partnered "with 375 food programs throughout Washington to create" the Hunger Response Network.

Programs & Initiatives

- For 2021, its legislative agenda priorities are expanding SNAP's purchasing power, increasing resources for food banks, and supporting increased access to fresh food for low-income families. It also advocates for better funding for the Housing Trust Fund, affordable health care, and actions to promote economic stability.

- To handle the COVID-19 crisis, NWH called for additional volunteers among “high school seniors, college students, and furloughed workers, creating a workforce that can address the increasing need for food distribution services,” which was considered a best practice by FEMA. These volunteers helped fill meal boxes that were distributed at pop-up sites and Boys & Girls Clubs.

- The NPO sent over 500,000 emergency food boxes for distribution as a response to the pandemic. It also partnered with Second Harvest and Food Lifeline, forming the Washington State Partner Program, to meet the growing demand. The coordinated statewide effort developed a county-by-county strategy, with each county being matched with the most appropriate organization.

Impact

- The highly rated NWH provides an average of two million meals monthly through its "statewide network of 375 food banks, meal programs, and high-need schools. Northwest Harvest provides nutritious, culturally appropriate food to anyone in need, while respecting people's dignity and promoting good health."

- In the fiscal year of 2019, the organization distributed 24,8 million pounds of food to frontline hunger relief programs, and 76% of the food provided was fruits, vegetables, and protein.

- In 2020, the 20th annual Home Team Harvest campaign raised 23,552,116 meals for Northwest Harvest. “KING 5 and Northwest Harvest collaborated with partners AT&T, Safeway and Albertsons, Swedish and WARM 106.9 from October to December to collect cash and virtual donations. This year’s goal of 20 million was blown away thanks to generous support from the community, making this the largest Home Team Harvest yet.”

Hunger Free Colorado

- Hunger Free Colorado (HFC) is a statewide nonprofit organization founded in 2009 by the merging of the Colorado Anti-Hunger Network and the Colorado Food Bank Association. "Hunger Free Colorado leads efforts to connect families and individuals to food resources and fuel change in systems, policies and social views, so no Coloradan goes hungry."

- The organization aims to create systemic and sustainable solutions, based on “six core values: innovation, collaboration, respect, impact, equity and agency.” For most part, the organization acts like a bridge between different stakeholders, indicating it is a backbone organization for its community; however, it is not explicitly stated.

- Marc Jacobson is the CEO, and Lori Casillas is the COO. Suzanne Bruce is the Director of Development and in charge of the department; Elie Agar is the Director of Communications, in charge of the communications & advocacy department; Sandy Nagler is the Director of Strategic Partnerships, responsible for the corresponding department; at last, Brett Reed is the Director of Clients Services, in charge of the client services departments, which comprises all the programs offered by the organization. As it is standard, HFC also counts with a board of directors.

- Overall, HFC adopts referral services as a partnership model. Its partners include Kaiser Permanente, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Denver Health, state departments, among others. "Health care partners refer food insecure patients to Hunger Free Colorado. Hunger Free Colorado follows up with patients to offer food and nutrition services, and benefit application assistance." Kaiser Permanente also provided funding for the hotline and refer patients from multiple clinics to the organization.

- Other partners include the Colorado Health Foundation, Walmart Foundation, Whole Foods Market, MyTech Partners, Joy Wine and Spirits, and others.

- Funding comes from foundation and government grants (federal and state), corporate sponsorship, and private donations.

Programs & Initiatives

- Most HFC programs and initiatives are about forming a connection between the population and the resources already available, including initiatives aimed at partners/providers. Food policy is an important part of its strategy:

- The Food Resource Hotline is a toll-free number that connects Coloradans to the SNAP program, food pantries, and charitable resources. Available in English and Spanish.

- HFC offers multiple free resources, including research, best practices, guides and toolkit, and fact sheets. It released a simple guide to Coloradans in need of assistance, in English and Spanish, with available programs and resources, including a text-message service to find nearby food resources for those under 18.

- Hunger Through My Lens: This initiative aims to understand what hunger looks like and change public opinion and policymakers through photovoice, “an evidence-based, collective storytelling process that combines photography (and sometimes videography) and social action.” HFC released a step-by-step guide showing how to create and use photovoice to promote change, and hosts/promotes events for other organizations.

- Colorado Food Pantry Network "is a statewide effort that helps pantries invest in improved collaboration, organizational efficiencies and spur collective action."

- The Colorado Food Resource Collaborative (CFRC) is a quarterly meeting "for individuals and organizations working to eradicate hunger in our state. At these meetings, attendees have the opportunity to network, share ideas and challenges, and learn from one other."

- HFC started an outreach campaign with an immigrant-based community to encourage families to participate in child nutrition programs. In a report released in January 2021, the organization addresses immigrants' struggles, which account for almost 10% of Colorado’s total residents. The report is meant to be a road map for advocates and immigrant-serving organizations.

Impact

- HCF has not released detailed metrics for the year ending in 2020 (only the Form 990 is available). In its 2019 annual report, the organization presented its 10-year progress.

- In 2020, the organization connected more than 21,000 individuals to food resources. It built and sustained a network of 36 partner organizations and helped individuals submit 9,689 SNAP applications. In 2019, the total number of SNAP applications was around 5,000.

- In 2020, the CFPN membership grew to 100 pantry members “working together to share resources and develop sustainable ways of obtaining the nutritious food pantry clients want and need for their pantry inventory.” It developed an online communication system to allow pantries to share best practices and information, which was valuable when COVID-19 started to impact food supplies. Through its advocacy, HFC secured $500,000 for the Food Pantry Assistance Program from state funding to be distributed by the organization to multiple partners.

- To address child nutrition issues, it partnered with stated agencies, school districts, communities, and non-profits to “increase participation in summer meals, school meals and WIC nutrition programs.” HFC started an outreach campaign with an immigrant-based community to encourage families to participate in child nutrition programs.

Organizations that are a Part of a Continuum of Care Program

Three Rivers Community Action & River Valleys Continuum of Care

- Founded in 1966 by local citizens, Three Rivers Community Action nonprofit human service organization that covers Minnesota’s Southeast Continuum of Care region. The organization works with community partners to provide "warmth, transportation, food, housing, advocacy, and education to individuals and families across southeastern Minnesota."

- It serves primarily low-income families, in a variety of ways. Three Rivers has “grown over the past 50+ years from serving 100 clients to over 15,000 people each year. The agency's operating budget has increased from the original $60,000 federal grant to over $12 million, including federal, state, local and private resources.”

- Three Rivers "assists the CoC in two ways: It acts as the employer of record for River Valleys CoC staff and it acts as the Collaborative Applicant (eligible entity) for federal CoC Program funds because the CoC is an informal collaborative." River Valleys CoC's 2021 organizational chart:

- All partners under the River Valley CoC must “provide connections to mainstream and community-based emergency assistance services such as supplemental food assistance programs and applications for income assistance.”

- In 2020, the River Valleys CoC counties were awarded State Set Aside (SSA) funds under the Emergency Food and Shelter Program (EFSP). A local board “comprised of representatives from the four-county area make recommendations to determine how the funds awarded to each county are to be distributed among the emergency food and shelter programs run by local service agencies in the area.”

- For the year that ended in December 2019 (the last one released), the organization received $16.8 million in funding, mostly through federal and state grants and rental income. Most of this revenue goes towards housing and transportation programs.

Programs & Initiatives

- The organization has nine main programs: Head Start, Transportation, Energy Assistance, Weatherization, Housing Development, Family Advocacy Services, Older Adults, and Continuum of Care (CoC). Each has its own department and staff.

- Head Start is a preschool program “focusing on child development and serving 3- and 4-year-old children and their families. Head Start establishes relationships that promote growth and development in young children and encourages the self-sufficiency of families.”

- Transportation: Cheap scheduled transportation within city limits. The organization encourages businesses to advertise on its buses.

- Continuum of Care: "Twenty-county planning body preventing, responding to and ending homelessness; securing federal, state, local funds for homeless assistance."

- Energy Assistance provides "a starting place for individuals and families looking for various kinds of help. The program offers financial aid, crisis intervention, system repair and replacement, and referrals to the Weatherization and other human service programs. The Weatherization program is the next step in reducing energy costs and becoming increasingly energy efficient, and provides households with an energy audit and subsequent energy efficiency upgrades."

- The Weatherization Program is "administered by Three Rivers Community Action, Inc. and funded by the Minnesota Department of Commerce along with many area utility companies. This program runs year round to reduce eligible households' energy costs and improve the comfort level of their homes. It is a grant program, which means the eligible work is done at no cost to the household."

- Housing development activities includes "building, preserving and owning rental housing, assisting people with homeownership needs, and providing homeowners with resources for improving their homes."

- Family Advocacy Services: It connects "individuals and families with resources and partner organizations and develop personal relationships through customized and comprehensive service." The Family Advocacy Services Department participates in the "Southeast Minnesota River Valleys Continuum of Care Coordinated Entry System (CES), for housing and support services for the homeless." It also includes "outreach and application assistance" for the SNAP program.

- Older Adult Services assist "individuals aged 60 and older and their families with information, referrals, and resources that allow persons to remain healthy and independent in their homes and communities. These services help families of all incomes, and a small donation is requested when services are provided. Families must have at least one member residing in Goodhue, Rice, or Wabasha counties."

- Achieve Homeownership is a "collaborative program that identifies and addresses barriers to homeownership faced by diverse households across southern Minnesota. It provides culturally-tailored financial and homeowner education and counseling services that are essential for successful first-time homeownership."

- Meals on wheels is a part of the Older Adult Services program, and delivers meals to "people over 60 or disabled who are home bound and have difficulty preparing their own nutritious meals."

- The meals are "provided by local caterers and delivered by volunteers. In addition, program coordinators meet with each individual to discuss nutrition and other services available to aid them in remaining independent."

- The funding is provided by the Southeastern MN Area Agency on Aging, United Way Rice County, United Way of Goodhue, Wabasha and Pierce Counties, Community Funds, Civic Organizations, such as American Legions and Lions Clubs, and private donations.

- The organization does not charge for meals but encourages donations ($4.50/meal for those over 60 and $7,00/meal for those under 60).

Impact

- Three Hill’s 2020 impact report is divided by county:

- Goodhue County Highlights: 1, 243 households served in 2020, 43% of which were below the poverty line. 12,575 meals distributed to residents. A summary of the full impact in Goodhue County can be found here.

- Olmsted County Highlights: 2,546 households served in 2020, 46% of which are below the poverty line. Helped “578 households maintain housing stability through the COVID-19 Housing Assistance Program (CHAP).” A summary of the full impact in Olmsted County can be found here.

- Rice County Highlights: 1,468 households served in 2020, 44% of which are below the poverty line. Volunteers delivered 18,560 meals to residents. A summary of the full impact in Rich County can be found here.

- Wabasha County Highlights: 552 households served in 2020, 43% were below the poverty line. Volunteers delivered 5,087 meals to residents. A summary of the full impact in Wabasha County can be found here.

- In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, “Three Rivers established a new Cares Fund that assembled new resources to provide direct assistance to individuals and families affected by the pandemic. Agency wide this assistance helped 1,015 households with a housing, transportation, utilities and other urgent needs.”

Meals on Wheels

- Meals on Wheels (MoW) is "the leadership organization supporting the more than 5,000 community-based programs across the country that are dedicated to addressing senior isolation and hunger." It is part of continuum care programs in multiple states, including River Valleys CoC.

- MoW is a nonprofit organization chartered in Washington, D.C, in 1976. Most of its activities are funded with corporate, foundation, and government grants and individual contributions, one annual conference, and membership fees.

- Its board of directors is composed of AARP and Senior Citizens Inc. directors and officers from MoW's selected chapters. Ellie Holland is the CEO.

- Local Meals on Wheels programs “provide home-delivered and/or congregate meals to seniors across the United States and have long been attuned to the needs of their local communities. This local focus enables programs to plan for and respond to the unique needs specific to their communities — one of the most powerful attributes of this national network.”

- Twenty-percent of local programs serve rural communities. Two-thirds of the seniors served by MoW are at or “below the poverty line, with one-third having a monthly income of less than $1,000.” These programs also serve more than 475,000 veterans.

- Thirty-nine percent of MoW’s funding comes from the Older Americans Act. The other 61% comes from diversified sources, such as state grants, private donations, corporations, and federal block grants. Despite years of success, the organization cautions that the funding are not keeping up with the demand for services, as costs have increased while funding remains stagnant, resulting in 20 million fewer meals per year.

- The MoW strategy and impact team provides members thought leadership, research, programming tools, grant opportunities, and data analytics. One of the initiatives of the team is MoW Health.

- The membership team provides members “advocacy, education and training, program and capacity building support and networking opportunities” to members. It also provides “grants and revenue distribution services and other peer-to-peer learning programs.”

- The marketing and communication team raises “visibility of the hidden and growing Nationwide epidemics of senior hunger and isolation.”

- Lobbying activities include mailing via e-mail and social media and “direct contact with Congress members, their staff, and administration officials through meetings, letters, e-mails, briefings, and public policy events.”

Impact

- When the pandemic hit, seniors were the most vulnerable group and in need of urgent support. MoW delivered 19 million additional meals to 1 million additional seniors. As reported by the organization, “By July 2020, the Meals on Wheels COVID-19 Response Fund enabled us to successfully scale our efforts to serve 47% more seniors than pre-pandemic and increased the number of meals we distributed by 77%.”

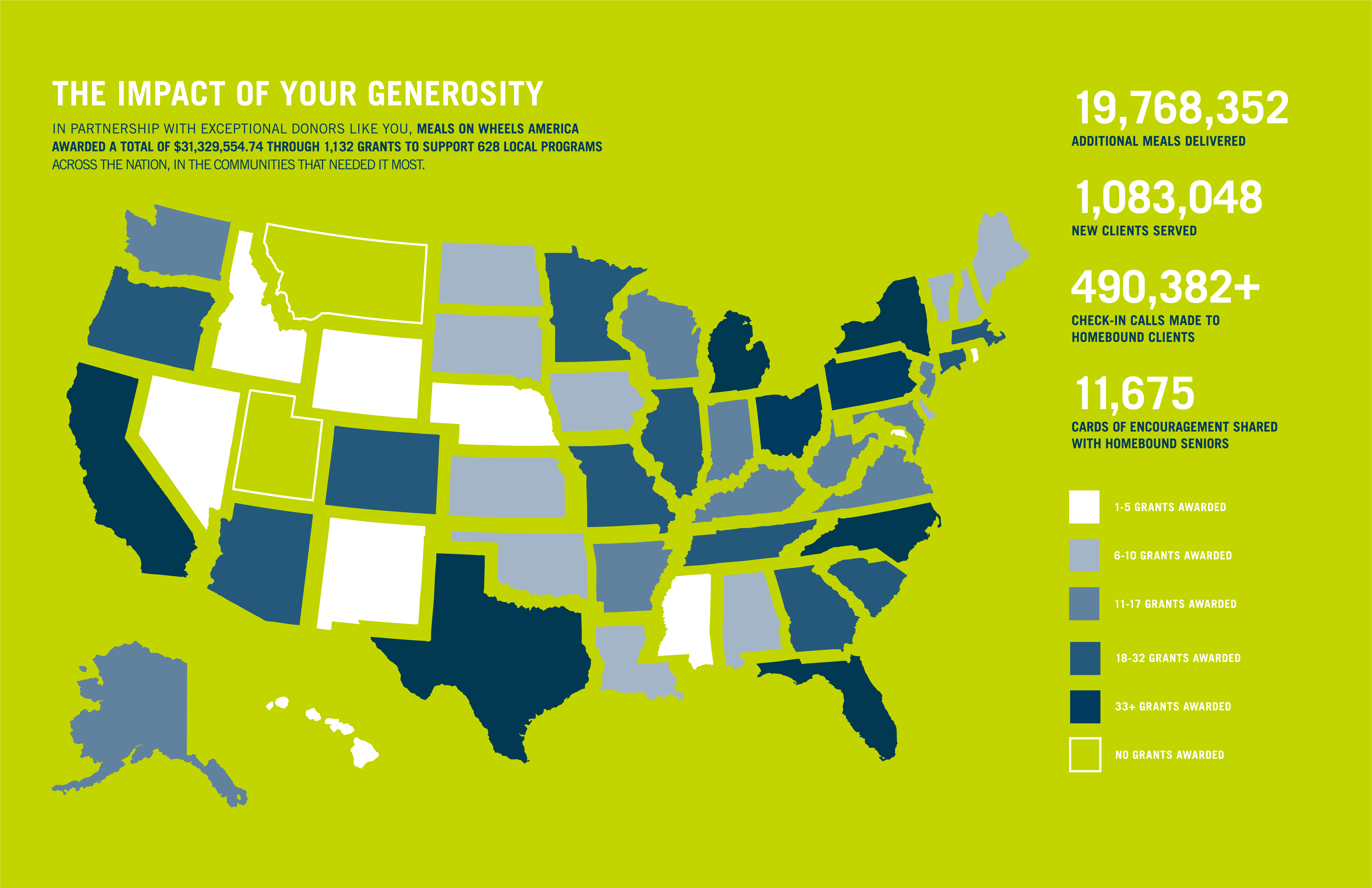

- It sent "$31.3 million directly to the frontlines during the pandemic. That’s more than 1,000 grants to support 628 local communities. Our impact spanned the nation and went into the communities that needed it most."

The Inter-Faith Food Shuttle

- The Inter-Faith Food Shuttle is a nonprofit organization based in North Carolina. It recovers and distributes food to low-income neighborhoods and provides learning opportunities and additional support to young members of the community. It is part of United Way North Carolina.

- With a particular focus on families living in food deserts, the organization partners with churches and community housing to create Mobile Markets in which low-income families can shop for free. The organization tries to bring fresh products to families, particularly for seniors and children. Some fresh products are grown on Food Shuttle's own farm.

- It collaborates with over 200 agencies, schools, and community centers to reach over “60,000 adults and children struggling with hunger receive healthy food every month. Additionally, more than 7,000 individuals participate in our cooking and gardening programs, strengthening their self-sufficiency, increasing their consumption of fresh produce, and becoming more food literate.”

- The Food Shuttle operates in a "seven county service area in central North Carolina, including: Wake, Durham, Johnston, Orange, Chatham, Nash and Edgecombe counties."

- Staff drivers and volunteers recover food daily from “retailers, markets, wholesalers, farmers, and community food drives. 80% of this food is immediately distributed to partner pantries, soup kitchens, institutional kitchens, and other human service agencies.” In total, the organization recovers food from 350 donors, including Walmart, NC State Farmers Market, Trader Joe’s, and Sam’s Club. Additionally, Food Shuttle also purchases products for the programs that require more food with consistent quality on a weekly basis, such as BackPack Buddies and School Pantries.

- According to L Ron Pringle, the CEO, the organization's focus "not on the immediacy of hunger, but rather the underlying systemic issues that contribute to generational poverty. Through collaborative efforts, we will continue engaging in intentional community organizing work."

Programs & Initiatives

- Hunger relief programs:

- BackPack Buddies: This program provides "children from food-insecure homes with healthy weekend meals during the school year."

- Grocery Bags for Seniors: This program aims to supplement the fixed incomes "of older adults through door-to-door distribution of fresh produce and groceries."

- Mobile Markets: One of the programs that differentiate the organization, "Mobile Markets," prepares "direct distributions of groceries and fresh produce, designed to meet people at their point of need."

- School Pantries: The program provides "fresh produce, meats and non-perishable foods to students, staff, and community members at 28 schools in Durham, Edgecombe, Johnston and Wake counties."

- The Mobile Tastiness Machine: Offers free healthy meals to children during the summer to balance out school meals not being available.

- Community Health Education:

- The organization is “the largest implementation partner in North Carolina for Share Our Strength's nutrition education program, Cooking Matters. As part of the No Kid Hungry campaign to end childhood hunger in America, the Cooking Matters and Cooking Matters at the Store curriculum teaches participants to shop smarter, use nutrition information to make healthier choices, and cook delicious affordable meals.”

- As a response to the Pandemic, the Cooking Matters program became “Cooking Matters at Home” webinars. Participants also receive a $10 Food Lion gift card. The program counts on volunteers to present the webinars.

- The Urban Learning Gardens program maintain two urban gardens to teach citizens “growing techniques, food production, bee pollination, and health education.”

- The "Gardens For Everyone" project is for anyone "interested in having a home garden in Wake or Durham County. Priority is given to low- to moderate-income households, as well as organizations in this area that want to grow food for their community. Applications are accepted year-round."

- Community Partnerships: The organization matches local agencies with retail donors based on “needs of those they serve.”

- Horizon Catering: This program aims to create a practical partnership between corporations and Inter-Faith Food Shuttle by offering catering services. Products are sourced from the Food Shuttle Farm. According to the organization, the partnership “between the Farm and Horizon Catering is a mutually beneficial one, and benefit Inter-Faith Food Shuttle through revenue generation opportunities that help support the organization as a whole. One dollar spent with Horizon Catering, or one product purchased from The Farm means we are able to continue to help those in need. The intangible benefit of The Farm is the opportunity it offers for volunteers to directly help Inter-Faith Food Shuttle work toward the goal of ending hunger in NC through hands-on efforts.”

Impact

- 2019 Impact:

- 2020 Impact:

Government Entities

Prince George’s County Food Equity Council

- Located in Maryland, Prince County is one of the highest-income Black-majority counties in the United States. In 2015, the county’s Planning Department reported health disparities, showing that residents living in urban areas had higher rates of diet-related illness. Prince county is a food swamp. To address this issue, the county established the Food Equity Council (FEC).

- Since its launch in 2013, "the FEC has pursued multiple policies to address inequities in the local food system associated with food swamps and lack of access to healthy food. The county’s FEC is one of the few food policy councils in the U.S. that intentionally includes the term 'equity' in its name."

- It provides a "forum for community engagement in Prince George’s county and a platform to amplify the voices of those most affected by policies focused on achieving equitable food access. Similar to the makeup of other food policy councils, the membership includes representatives from a broad coalition of anti-hunger, direct service, and advocacy groups, grocery stores, government agencies, community-based organizations, civic associations, urban and rural farms, agricultural service providers, universities, and health care providers."

- The FEC was endorsed and funded by the county in 2013. It was later “incubated and is currently housed within the Institute for Public Health Innovation (IPHI). The role of IPHI is to ensure that the FEC has the capacity and support it needs to be productive and sustainable and to provide financial and administrative support as its fiscal sponsor.” Its funding comes from the County Council Non-Departmental Grant and Kaiser Permanente of the Mid-Atlantic States.

- The FEC is staffed by a "part-time Director and receives technical assistance from the Coordinating Committee. The Coordinating Committee includes Institute for Public Health Innovation staff members and consultants that provide ongoing technical assistance, logistical support, and guidance in collaboration with its internal leadership structure."

Programs & Initiatives

- The FEC is focused on policy change and nutrition that "address multiple dimensions of food access that advance equity in diet-related health outcomes." The following chart showcases some of its initiatives:

- It currently serves as the chairing organization “of the Healthy and Safe Food Subcommittee of the program’s Oversight Committee.”

- On January 25, 2021, FEC joined “the Food Rescue US network to launch the Food Rescue US platform in Prince George’s County. The county’s food recovery efforts will be coordinated by FEC staff and funding from the Greater Washington Community Foundation and Philip L. Graham Fund.”

- According to the press release, in 2020, “the FEC’s work has taken on a new urgency as the COVID-19 pandemic caused skyrocketing rates of food insecurity and high demand for food among food assistance providers and social service organizations. According to the Capital Area Food Bank, over 104,760 county residents were food insecure in 2020, the highest in the Metro DC Region. By developing a robust food waste and recovery network, IPHI, FEC, and Food Rescue US hope to create a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable food system that can support the growing number of food-insecure residents.”

- Over the next few months, "FEC staff will conduct outreach among businesses, organizations, volunteers, and providers to expand the Food Rescue US network in the county and bring partners onto the platform."

Impact

- According to the Healthy Food Policy Project, these policies “represent the FEC’s commitment to equity within the local food system—increasing access to healthy food for those most impacted by health disparities and improving economic opportunities for urban farmers. Specifically, it is anticipated that these policies will lead to an increase in SNAP recipient purchases of fruits and vegetables at farmers’ markets, a larger availability of culturally appropriate produce through urban farm operations, and a greater consumption of healthy vending products on government property.”

- Thanks to FEC's advocacy, Prince County became the first in the country to pass a comprehensive healthy kids' meal legislation that "will make healthier drinks the default beverage options and limit calories, sugar, salt, and fat for all kids' meals served in Prince George's County restaurants."

- The FEC was one of "the leading organizations for the County's COVID-19 food assistance response," coordinating efforts between partners and County agencies to support residents. In one month, it distributed over 10,000 meals; helped residents connect to assistance providers; launched an online food assistance directory, which got 13,000 hits in its first month; co-hosted bi-weekly virtual meetings for 70 food assistance providers and partners; among other actions.

Madison Food Policy Council

- The Madison Food Policy Council (MFPC) is a part of the Mayor’s Office, and advises the Mayor and the Common Council. Its mission is to “drive policies, programs, and collaborative resources relative to support the development of a sustainable local and regional food system that supports equitable access to healthy, culturally appropriate food, nutrition education, and economic opportunity.”

- The council counts with 23 members, representing "key areas of the local and regional food system," including resident members, common council, school district, small or mid-sized retailers, urban farms, food systems expert, community gardens, local restaurateur, university of Wisconsin, healthcare providers, and direct Market producer representative. Some positions are vacant.

- The MFPC conducts the "bulk of its policy and program work within the structure of work groups. Because of the COVID-19 Pandemic, the MFPC and our County counterpart, the Dane County Food Council, created and adopted a unified COVID-19 Framework, which has launched joint work groups, streamlined our meeting procedures as a joint process, and created closer collaboration between the City and the County on community food systems issues during the pandemic and beyond."

- In the new structure, the following teams work together: Food Waste & Recovery, PIE Grants, and Urban Agriculture.

- The Community Engagement team, Health Retail Access team, Healthy Marketing & Procurement team, SEED Grants team, and Equity and Access team remained county-exclusive.

Programs & Initiatives

- The Council is currently exploring “opportunities for FEMA reimbursement to restaurants and food businesses through a recent Biden executive order which makes expenses for hunger prevention a reimbursable expense.”

- Working with school districts to “understand Pandemic EBT benefits and how families may benefit from this program, including retroactive payments to low-income families that fed children at home.”

- Madison also "allocated previously authorized funds for partnership with designated groups that are prioritizing COVID-19 needs via local produce use. For example, one of the partner organizations is using $4,500 to fund meal deliveries and food boxes with local produce."

- On April 21, 2020, the “City of Madison Common Council approved $50,000 in funding for 13 community-based organizations working to alleviate food security and access issues for residents dealing with the economic fallout of COVID-19. The Madison Food Policy Council adapted the original SEED Grants program, which historically funds food education and access projects in the City, and created a COVID-19 funding application to assist organizations implementing programs to serve residents affected by COVID-19.”

- These funds were redirected from the Healthy Retail Access Program to support the “(1)Community Food Access Competitive Grants Program, (2) Rapid Food Access and Food Entrepreneur Support Program, and (3) provide funding to the Madison Food Policy Council to begin a regional food systems planning process.” This strategy was considered an example to be followed by the Healthy Food Policy Project.

Impact

- The City of Madison’s 2021 Budget now "includes $150,000 in grant funds to be distributed by the Madison Food Policy Council, with individual grants capped at $25,000."

- The 2021 Community Food Access Competitive Grants Program “provides funding to community-based organizations that are creating a healthier food system in Madison and addressing the increasing food insecurity and food access disparities that community residents are facing during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Priority is given to proposals that address food insecurity, social justice and racial equity, and include a plan to evaluate program success and impact.