Part

01

of one

Part

01

Critical Thinking (2)

Key Takeaways

- Critical thinking is the ability to question and reflect rationally, eliminating reasoning biases to arrive at an evidence-based conclusion or assumption.

- For companies and business leaders, mastering critical thinking is essential to be on top of market fluctuations and trends, and avoid mistakes created by miscalculated forecasts or biased assumptions. Additionally, it can help predict growth opportunities.

- The ACER model breaks critical thinking into three different strands: knowledge construction, evaluating reasoning, and decision-making. Each strand requires a self-analysis of the information and logic used to draw conclusions.

- The PACADI model determines six-steps to develop critical thinking based on the case method: problem definition, identification of alternatives to address the problem, the establishment of criteria to guide decision-making, in-depth analysis of alternatives, justification of the decision-making, and examination of the implementation.

- The three-stage model, commonly recommended by universities, only requires three steps, guided by critical questions: description of the problem/situation, analysis of the reasons and causes, and evaluation of implications and conclusions.

- Practical actions and habits that can help develop critical thinking include seeking critical feedback, weighing different perspectives, and replacing negative introspection with self-awareness.

As the market evolves and technology progresses, business leaders and companies need to adapt to changing consumer behaviors and market fluctuations, requiring fast decisions. Critical thinking is imperative to ensure the decision-making process is unbiased and evidence-based. There is limited information available regarding the actual impact of critical thinking, apart from qualitative insights. Furthermore, excluding learning and development companies resulted in minimal options for models. Details surrounding our methodology can be found in the research strategy section.

Critical Thinking - Theories and Definition

- From its inception in the 70s to its "buzzword" status today, critical thinking "strongly resists the theoretical conceptualization." Scholars note that there have been many attempts to define what it means, and "with each new appearance, critical thinking becomes less, rather than more, clearly defined."

- However, it is somewhat accepted among researchers that critical thinking is the “concept of rationality and the ability to engage in unbiased reasoning.” The unbiased aspect is of particular importance, as biases crack the entire chain of thinking. The dual mode process explains how biased/unbiased reasoning happens:

- The model believes that there are two types of cognitive processes involved in one’s reasoning process: Type 1 and Type 2. Type 1 processes have “automatic nature, involve little reflection, and impose a relatively low load on working memory. Decision-making using Type 1 processes, is based on past experiences, which is useful and efficient in many routine situations. However, because of its automaticity, it might result in biased thinking in other, non-routine situations.”

- Type 2 processes are “deliberate, and sequential in nature, and impose a higher load on working memory than Type 1 reasoning.” Ideally, Type 2 processes overrule the automatic responses created by Type 1 processes by “explicit reasoning efforts.” Type 2 reasoning can be divided into algorithmic and reflective processes.

- Reflective processes: “associated with beliefs, cognitive styles, goals, and epistemic values and thinking dispositions.”

- Algorithmic process: “associated with analytic and inhibitory operations and with decoupling beliefs from evidence.”

- The algorithm mind can overturn Type 1 processes by “applying knowledge of inferential rules and strategies of rational thought (e.g., probabilistic reasoning, causal reasoning and logic). Biased reasoning arises when Type 2 reasoning fails to override Type 1 reasoning in situations in which Type 1 reasoning is insufficient.” These failures happen due to lack of "declarative knowledge" or "insufficient develop strategies, such as hypothetical thinking," which means that even when knowledge is present, insufficient cognitive simulations can lead to biased conclusions.

- There are three main approaches to critical thinking: “skill-oriented perspective,” “person-oriented perspective,” and “social norms-perspective.” One paper examined the three theoretical approaches and concluded that, in business education, a social norms-centered approach “appears to be the most adequate as it does not smother ‘ideological’ or ‘normative’ nature of the critical thinking concept.” Therefore, the business application of critical think needs to go beyond theory and consider real-life events and applications, which is one of the reasons why business schools tend to use the case method to teach critical thinking.

- Regardless of the different theories surrounding, critical thinking is essentially the ability to question and reflect. “It is thinking in the one sense of inferring or deciding and in another sense of questioning (evaluating) inferences or decisions in the face of our authentic experiences.” Or, as Stanford defines it, "careful goal-directed thinking."

The Impact of Critical Thinking

- The ability to engage in “unbiased reasoning is crucial for decision-making in complex and high-risk professions.” In complex industries, such as finance, it is imperative to assess potential impacts of market tendencies, new regulations, and current events. The lack of leadership with critical skills can result in the institution “losing profit or even suffering legal consequences from non-compliance.”

- Biased reasoning can lead to numerous wrong decisions with severe consequences, and importance of critical thinking becomes evident when examining the consequences of its absence. For example, Ireland’s 2008 banking crisis has been “been associated with a number of cognitive biases leading to the underestimation of risks by stake-holders.” The lack of critical thinking led to overly optimistic forecasts, “and stockbrokers have been demonstrated to engage in irrational thinking, drawing invalid conclusions guided by prior knowledge and beliefs instead of logical reasoning.”

- According to Deloitte, focusing on skills alone is “yielding less return” for businesses for two reasons. One, the evolving market and consumer behavior means that the skills required are evolving faster than the workforce’s ability to learn. Two, standardized skills are not developing a long-term relationship with consumers. The consulting giant suggests that a workforce with “enduring human capabilities,” such as critical thinking, is more adaptable and better equipped to handle the "rapid learning that is required to thrive in an environment of constant disruption."

- Critical thinking allows leaders to spot growth opportunities before their competitors, as they are able to stay ahead of market trends, spot growth opportunities, and improve strategies. Additionally, it can avoid hasty decisions and miscalculations.

- As an example, an article published in 2005 by the Harvard Business School noted that Netflix was able to disrupt the rental store model because Reed Hasting challenged conventional wisdom with critically evaluated assumptions. The author already recognized Netflix as an example of critical thinking before the company launched its streaming service in 2007.

- Leaders are also not immune to the disruption caused by automation. As AI becomes more developed, higher cognitive skills, such as critical thinking, will be in demand, as technology is still many years away from developing an AI that can replace the critical thinking of a human.

- Garth Saloner, dean of Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, explains that, while harder skills of finance and supply chain management and accounting are standard for MBA graduates, soft-skills of leadership and critical thinking are still in “very scarce supply.” Critical thinking skills are a currently a priority in reskilling programs:

- It is also possible to note the importance of critical thinking for leaders by analyzing the consequences of its absence. For example, because of biased reasoning, business leaders have been shown to "neglect relevant base-rates and to be overly confident in starting a firm and doing business."

- Additionally, those without critical thinking skills “tend to consider only information which matches the lexical content of a statement about which they are reasoning as being relevant, and conversely, tend to neglect logically relevant information.” This is correlated with matching biases on selection, which is a topic of particular relevancy in the current climate.

- They are also more prone to “to show erroneous judgments and reasoning on causal and probabilistic tasks, assessment of covariation tasks, framing tasks, and conjunction tasks.”

Mastering Critical Thinking - Models & Tools

- There is limited publicly available information surrounding reputable critical thinking models that individuals could use without the assistance of an academic environment, or that are not developed or directly linked to learning and development companies (the reasons behind this fact are detailed in the Research Strategy Section). The following frameworks are academic models designed to assist students. They are more complex than desired, but could potentially be adapted to individuals and business leaders due to their step-by-step nature.

ACER

- Developed by the Australian Council for Educational Research, the ACER critical thinking framework defends that practical critical thinking requires a broader set of skills than the typical “analyze, self-regulate, and evaluate.” A combination of core critical thinking skills must be applied simultaneously to produce results. The model comprises three strands. Each strand contains three elements.

- The first strand relates to “to the kind of reflective and evaluative engagement with information that is required to make accurate sense of it. It involves establishing what we know and what we need to know, what information seems plausible, useful and reliable, and how it can best be organised to derive explanatory sense and meaning from it.” The first strand requires three steps, identified as aspects (summarized version - the source presents a detailed explanation of each aspect):

- Aspect 1.1 refers to the identifications and understanding of one’s own knowledge surrounding a topic, recognizing its limitations and misconceptions. Aspect 1.2 determines which sources or pieces of evidence should be used in the decision-making process, distinguishing fact from opinions. Aspect 1.3 surrounds one's ability to reflect and organize on the information gathered through analysis and the construction of patterns and connections.

- The second strand, “evaluating reasoning,” concerns the “thinking required to discern the validity of arguments, scientific theories, statements, proofs and other formulations of ideas. It involves analyzing and evaluating verbally-constructed arguments, sets of propositions and other non-verbal representations of information and relationships to identify the premises that underpin a conclusion or truth claim, judging the logic of how conclusions are reached, and ensuring one’s own arguments or formulations are sound. Reasoning itself can be represented in a variety of forms such as verbal, spatial, abstract, numerical, mechanical, algorithmic and graphical. When working in complex problem-solving contexts, a variety of representations of reasoning may be present.”

- Aspect 2.1 refers to the application of logic through a set of premises required to arrive at a logical conclusion. Aspect 2.2 examines assumptions and motivations of the reasoning to identify biases. Aspect 2.3 justify the arguments used to draw conclusions, requiring “an ability to explain the evidence and reasoning that leads one to make a claim.”

- The third and final strand, “Decision making,” is analytical and evaluative, and does not require creative thinking, thus “aligning more neatly within a framework of critical thinking.”

- Aspect 3.1 identifies the situation and the criteria required for an effective decision. Aspect 3.2 analyzes the options and alternatives against the previously established criteria. Aspect 3.3 tests the effectiveness of the decision, its impacts, and implications.

- The method is based on evolution. As critical thinking skills are developed, learners move through three different levels (low, medium, and high). For example, the following table shows knowledge construction levels. Other strand levels can be found here.

PACADI

- Based on research in higher-education environments, critical thinking models are more likely to be effective when combining explicit rule training with real-life application guidance. This conclusion was based on multiple experiments made in the last decades. Case Method is often considered the most effective way of combining both in the developing critical thinking.

- For example, it is the basis of the methodology of the critical thinking course at Stanford. The case method may not be the best option for a simple model; however, the PACADI framework, developed by Harvard professors to help students solve case studies, contains steps that could be applied to real-life decisions.

- This method could be beneficial for those trying to break old vices, as it is based on the assumption that students do not have practical experience, therefore, need guidance to develop critical thinking. Additionally, it is based on real business case studies, which is nothing more than a simulation of real-life situations.

- PACADI stands for Problem, Alternatives, Criteria, Analysis, Decision, Implementation. It is a step-by-step "decision-making approach that can be used in lieu of traditional end-of-case questions. It offers a structured, integrated, and iterative process that requires students to analyze case information, apply business concepts to derive valuable insights, and develop recommendations based on these insights."

- Step one — Problem definition: This step explains and explores the problem at hand. “What is the major challenge, problem, opportunity, or decision that has to be made? If there is more than one problem, choose the most important one. Often when solving the key problem, other issues will surface and be addressed.” Research shows that self-explaining is an effective method to develop critical thinking. Additionally, the Harvard professors believe that forcing students to identify the main problem results in a more in-depth analysis as they “peel back the layers of symptoms or causation.”

- Step two — Alternatives: One must identify alternatives to address the problem. Preferably between two to five alternatives. More importantly, alternatives should be “mutually exclusive, realistic, creative, and feasible given the constraints of the situation. Doing nothing or delaying the decision to a later date are not considered acceptable alternatives.”

- Step three — Criteria: One must define what “key decision criteria will guide decision-making.” The method asks students to discuss their rationale for selecting the criteria and “the weights and importance for each factor.”

- Step four — Analysis: One needs to conduct “an in-depth analysis of each alternative based on the criteria chosen in step three.” They propose several tools that can help, such as creating decision tables using the criteria as columns and alternatives as rows; pros and cons lists; best, worst, and more likely scenarios studies; and lists of short- and long-term implications of each alternative.

- Step five — Decision: Final decisions should be justified based on the analysis, correlating the recommendation with the previously chosen criteria. It forces the reexamination of the previous steps.

- Step six — Implementation of the plan: According to the professors, “Sound business decisions may fail due to poor execution. To enhance the likeliness of a successful project outcome, students describe the key steps (activities) to implement the recommendation, timetable, projected costs, expected competitive reaction, success metrics, and risks in the plan.” This step could help further analysis of the implication of the decision-making process.

- The structured, “multi-step decision framework encourages careful and sequential analysis to solve business problems,” a process business leaders must exercise daily.

Three Stages Model

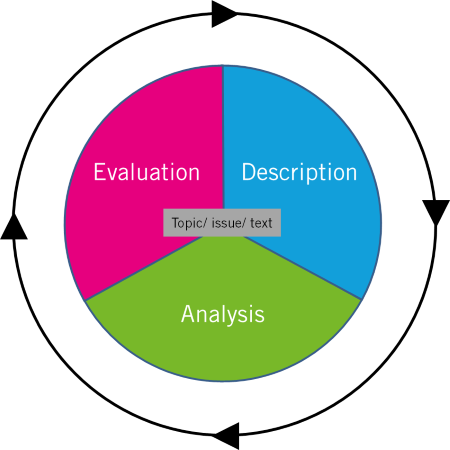

- The three stages model is widely used by universities to exemplify and guide students through the critical thinking process. It involves a series of questions that should be made during three phases: description, analysis, and evaluation.

- At the first stage, Description, one must establish background and context by asking simple questions: "What? Where? Why? and Who?" For example, when examining a problem, a leader should ask, “What is this problem about?” “Who does it involve or affect?” “When and where is this happening?” These questions have the goal to lead to explanatory answers, resembles self-explaining.

- The self-explanation technique is a “a domain-general constructive activity of explaining instructional materials to oneself, which engages students in active and meaningful learning while they effectively monitor their understanding.” The act of explaining something assists in the identification of “comprehension failures, integrating new information with prior knowledge and repairing faulty knowledge.” This technique is widely applied in higher-learning, as a way to develop critical thinking.

- The second stage is Analysis. Here, the questions change into “How? Why? And What if?” The goal is to examine “methods and processes, reasons and causes, and the alternative options.” When analyzing a problem, a business leader could ask, “What are the contributing factors to the problem?” “How might one factor impact another?” and “What if one factor is removed or altered?” Asking these questions helps break the situation into parts and consider the “relationship between each part, and each part to the whole”, thus enabling analytical answers and logical reasoning.

- The third and final stage is Evaluation. Its objective is to “make judgments and consider the relevance; implications; significance and value of something” by asking questions such as “So what?” and “What next?”

- Plymouth university uses the example of an archaeology student trying to make sense of a discovery to exemplify the process:

- The stages are not linear; one can go back and forth between the three steps.

Mastering Critical Thinking — Simple Steps & Tips

Five Steps

- Educator Samantha Agoos proposes five simple steps to improve critical thinking. Her method, published on TED-Ed and EPALE, is much more straightforward than the previous ones; however, it was not possible to track the credibility, hence why they were presented as a trick/tip, not a model.

- She argues that a decision should not be made just because “it feels right” but because the person used critical thinking to subject “all available options to scrutiny and skepticism.”The five steps are:

- "Formulate your question" one must question why they are taking a certain step or decision, trying to eliminate distractions or information that may obscure the real motivation behind a decision. A clear view of the objective can help to define the approach critically.

- "Gather your information": information should come from reliable sources. Gathering information allows individuals to weigh the different options available.

- "Apply the information": After gathering the information, one must ask critical questions, such as “what concepts are at work?” “What assumptions are being made?” and “Is my interpretation logically sound?’

- "Consider the implications": One should weigh short- and long-term implications and unintended consequences before making decisions.

- "Explore other points of view": This step concerns examining different viewpoints, even when they do not represent one’s beliefs. (this last step will be further explored in the subsequent tips as it is constantly mentioned by other relevant sources).

Seeking Critical Feedback

- As explained by business coach Debra Kasowski, exceptional leaders “reflect on their experiences and interactions with others. With every new experience, take time to reflect and journal out what was successful, what needs to be improved and what was learned.”

- According to an article published in the Harvard Business Review, when one has a clear vision of who they are, they are more likely to engage in positive social interactions and productive actions, thus becoming better leaders. The concept of self-awareness is complex, but some steps of its application are reasonably simple, such as asking for feedback.

- Evidence suggests that highly experienced and powerful leaders tend to be overly confident in their skills and experience, leading to a less accurate view of their own leadership effectiveness. Business professor James O’Toole notes that “as one’s power grows, one’s willingness to listen shrinks, either because they think they know more than their employees or because seeking feedback will come at a cost.”

- Successful leaders counteract this by actively seeking critical feedback from multiple actors. They become more self-aware in the process and are perceived as more effective by others.

- Forbes exemplifies the effectiveness of this step with research that shows that "Top-ranked leaders (those who average a score at the 83rd percentile on leadership effectiveness) are also at the top in asking for feedback."

- Forbes explains, "There is a significant change that occurs when people ask for feedback. When you ask others for feedback, your attitude changes. In contrast, frequently when others give us unsolicited feedback, our defenses are automatically raised. We debate, we rationalize, we react and then we finally reject the feedback. The very act of asking others for feedback puts us in a better position to listen carefully to the feedback, ask clarifying questions, and then accept the remarks."

Exposure to Different Perspectives

- Popular wisdom encourages individuals to seek and associated themselves with “like-minded people.” For a leader, surrounding oneself only with like-minded people creates an echo-chamber that is detrimental to the development of critical thinking.

- Leaders should engage and share their vision with people that have different perspectives. According to Forbes, people can always find ways to rationalize their point of view. However, without exposure to other perspectives, they may miss the fact that their viewpoint “may not offer the whole picture of a situation.”

- Helen Lee Bouygues, former partner at McKinsey, provides some tips into how leaders can expand critical thinking in their organization by seeking diversified perspectives: "In team settings, give people the chance to give their opinions independently without the influence of the group. When I ask for advice, for instance, I typically withhold my own preferences and ask team members to email me their opinions in separate notes. This tactic helps prevent people from engaging in groupthink." She also notes that leaders can expand their own critical thinking by actively seeking and engaging with people from different departments and career paths.

Introspection versus Self-Awareness

- Self-awareness is one of the basis for critical thinking. It is often assumed that self-awareness comes with introspection. However, according to organizational psychologist Tasha Eurich, “people who introspect are less self-aware and report worse job satisfaction and well-being.” She claims that only between 10-15% of people are truly self-aware.

- Introspection is not a bad thing. The problem lies in how people embark on the introspection journey. They ask “why,” which is an “ineffective self-awareness question.” Since crucial parts of the elements required for self-awareness are trapped outside of one’s conscious awareness, people tend to “invent answers that feel true but are often wrong. For example, after an uncharacteristic outburst at an employee, a new manager may jump to the conclusion that it happened because she isn’t cut out for management, when the real reason was a bad case of low blood sugar.”

- As previously noted, unbiased reasoning is not easy to achieve . The problem with asking why, argues Eurich, “isn’t just how wrong we are, but how confident we are that we are right. The human mind rarely operates in a rational fashion, and our judgments are seldom free from bias. We tend to pounce on whatever 'insights' we find without questioning their validity or value, we ignore contradictory evidence, and we force our thoughts to conform to our initial explanations.” Additionally, asking “why” opens the door to negative thoughts based on fears and insecurities instead of rational assessment of one’s weaknesses and strengths.

- The theory is complex, but the application takes a simple change of perspective. She proposes that instead of “why,” people should ask “what.” It is about searching for an actual plan based on critical thinking rather than analyzing abstract concepts and causes. When someone asks “why” a particular situation happened or “why” they are a certain way, they are more likely to waste time with denials and justification.

- When they ask “what” they are or “what” they could do to prevent a situation or implement a change, they see themselves and the situation more clearly. As researchers found, “Thinking about why one is the way one is may be no better than not thinking about one’s self at all.” Instead of asking "Why my employees are giving me negative feedback?" a business leader should ask "What steps are necessary to prevent this feedback in the future?"

Leadership and Critical Thinking

- Based on the Army Field Manual on Leader Development, a few signs indicate that a leader is incapable or is not applying critical thinking to his or her decisions. Applying the reverse logic to these attitudes and reasoning could be useful for those trying to develop critical thinking. (quoted verbatim from Forbes):

- "Signs of disorganization in thinking or speech

- Over-focus on details; inability to see the big picture.

- Lack of clarity about priorities.

- Inability to anticipate consequences.

- Failure to consider and articulate second and third-degree consequences of an action or decision.

- Inability to offer alternative explanations or courses of action.

- Oversimplification.

- Inability to distinguish critical elements in a situation from less important ones.

- Inability to articulate thought process including the evidence used to arrive at a decision, other options that were considered and how a conclusion was reached.

- Unable to tolerate ambiguity/over-certainty.

- Difficulty outlining a step-wise process to solve a problem or implement a change.

- Thinking that is driven by emotion or ego."

Research Strategy

According to multiple scholars, there is still controversy surrounding the effectiveness of the available models of critical thinking, particularly outside of controlled learning environments. There is also a lack of data regarding its real impact outside of classrooms. We were able to locate some qualitative insights, but hard data that measure real business impact, rather than importance, was not available. Two papers used in this report note the lack of empirical research surrounding the application of critical thinking in real-life.

Publicly available reputable sources, particularly academic research, tend to focus on developing critical thinking in higher-learning environments. Other reputable sources, such as consulting firms, contemplate the need/importance of critical thinking but not the real impact on businesses or models. Other alternative sources, such as business coaches, business thought leaders, and motivational speakers, usually present vague concepts that are not descriptive enough to be considered practical. For example, "don't overthink" is a common step proposed by these sources, but with no guidance of how one could practically address this mistake.

Credible outlets, such as the Harvard Business Review, have useful content, but the vendor restriction limits it. For example, multiple sources refer to the RED model as a framework for developing critical skills, as it is widely used by those going through selection processes that require Watson-Glass tests. Unfortunately, the RED model is associated with Pearson. Another example, an article published by the Harvard Business Review titled “A Short Guide to Building Your Team’s Critical Thinking Skills,” provides some step-by-step guidance. However, closer inspection shows that the article was written by Matt Plummer, founder of Zarvana, a company that offers critical thinking training for companies. Given the limitations, as an alternative approach,we chose three models that are not as simple or easy to follow as initially intended, but could potentially be adapted.